SHERIFF PETRAY AND 2 DETECTIVES KILLED Press Democrat Dec 6, 1920

On December 6, 1920 in Santa Rosa, California, the Sheriff of Sonoma county, James A. Petray and San Francisco Detectives Miles Jackson and Lester Dorman were gunned down. The killer was one George Boyd of Seattle, a professional boxer and a member of the so-called “Howard Street gang” of San Francisco.

George Boyd was wanted in connection with an “outrage” on a young woman in a house on Howard street in San Francisco around the end of November, 1920. The young woman was from Sonoma county. Boyd was not apprehended with the other 5 members of the gang and was on the run from the police.

Boyd had come to Santa Rosa with a local man, Terry Fitts, who was also wanted for questioning. According to a cab driver, Fitts was on a drunk and was acting strangely the day prior to the murder. He and and a man named Charles Valento went to San Francisco and met up with George Boyd and a woman named Dorthy Quinlan. The four returned to Santa Rosa, Fitts was trying to secure a loan for their getaway from Santa Rosa hotelier, Mr. Guidotti. It was in Guidotti’s home that the tragedy took place.

While they were discussing the loan, which was refused, the police officers showed up at the house.

Sheriff Petray was working with the two San Francisco Detectives canvasing the hotels and dive bars when they discovered where Boyd was. Taking a small contingent of 2 Deputies and 2 Santa Rosa Policemen, the Detectives and the Sheriff approached the Guidotti house from the front, while the other officers surrounded it, the Deputies going to the back.

Petray and the two detectives entered the parlor of the home and found Boyd and the three others. Boyd recognized Detective Jackson as a policeman who had arrested him years earlier, sending him to San Quentin. An argument ensued and Boyd, rising from the sofa, drew Fitts’ 44 Smith & Wesson hidden in the cushions and began firing. He shot Petray in the forehead and torso, and the two detectives each in the torso, Jackson taking two shots and one shot went astray. As Jackson fell, he shot Boyd in the side. Boyd rushed out the back door of the house with the now empty gun and was arrested by two Sonoma county Deputies. Fitts and Valento were also arrested.

The policemen assisted in getting the Detectives and the Sheriff to the hospital as quickly as possible. Sheriff Petray and Detective Dorman died at the house, Jackson was still alive and was able to give a deposition to the District Attorney a few hours later. There was another man, one Dan Fitz Gerald who was visiting the Guidotti home when the tragedy occurred and later gave a detailed deposition on the events.

The Quinlan woman and the wife of Guidotti also escaped out the back of the house as the gun fire erupted. Quinlan was found a few blocks away in a telephone booth at the Santa Rosa train station and arrested.

Later that night, Boyd was treated for his gun shot wound at the county jail. He was weak and in great pain and was kept in a separate cell from Fitz, Valento, and Quinlan. It was later discovered that the gun belonged to Fitts and that Valento had bought the box of ammunition.

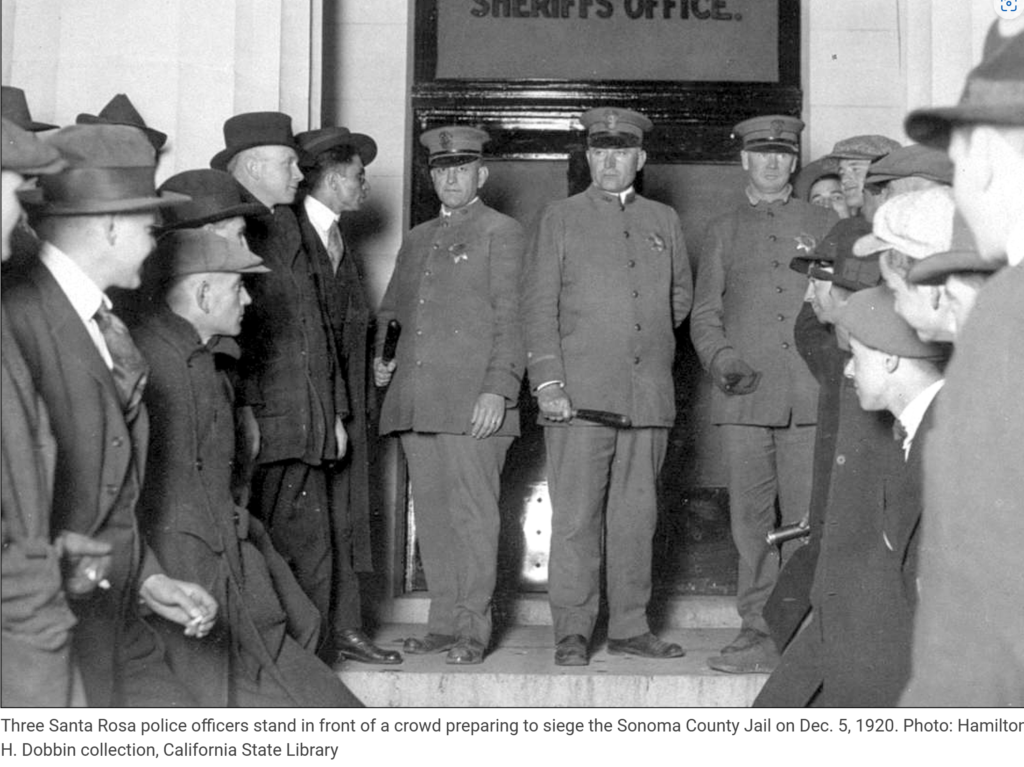

Word was circulated rapidly of the murders. That day, Sheriff Petray’s right hand man, Chief Deputy John M. Boyes, was chosen to fill the County Sheriff’s position by the Board of Supervisors and was sworn in at the county jail by Judge Emmet Seawell. The new Sheriff Boyes re-deputized all the existing deputies and was able to instill order to the jail and the department.

Many hundreds of onlookers took up vigil around the jail on a rainy night. The next day, Tuesday, December 7th, the crowd swelled to a few thousand and there were a couple of failed attempts to break into the jail to get to Boyd and his accomplices. One man was arrested during one attempt and booked for disorderly conduct. Santa Rosa policemen and Sheriff’s deputies held the crowd back. A plea by the Sheriff’s widow plus cold and heavy rain finally drove the crowd away by evening.

Various reactions to these events involved a “clean up” of sorts in both San Francisco and Santa Rosa. In San Francisco, by December 9th, 160 arrests had been made as part of the crackdown on crime. Also, during this time the Sonoma County District Attorney Hoyle was busy at work gathering witness testimony and building a case against Boyd for the murders.

Then, on December 10th, after the morning and afternoon funerals of Detectives Jackson and Dorman in San Francisco, a caravan of 15 to 20 cars left San Francisco heading north to Santa Rosa.

A group of armed and masked men cut the telephone lines to the jail, entered the now unguarded jail and forced Sheriff Boyes into his office, and, while holding jail staff at gun point, took his master key and located Boyd, Fitts, and Valento. They placed ropes around their necks and bound them, covered them with blankets and hustled them out of the jail. Fitts and Valento were gagged due to their protests. Boyd was in too much pain to either resist or cry out.

According to accounts in the Press Democrat, Sheriff Boyes pleaded with the lynchers to leave and let justice take its course. His pleas fell on deaf ears. There are other implications that the Sheriffs were willing to cooperate with the mob.

Outside a few of armed and masked men had cordoned off the jail to stop anyone from entering which included one or two local reporters. After their rebuff, the reporters made their way to nearby telephones and called the story into their newsrooms who then reported the events to the local police.

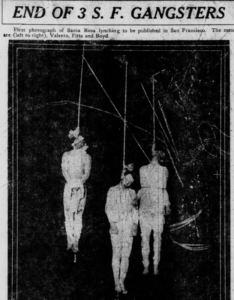

Around midnight, the mob formed up another caravan and drove to the Rural Cemetery on Franklin Avenue in Santa Rosa and quickly lynched the men from a large oak tree using their car headlights for illumination. Guards were stationed around the cemetery streets and locals, aroused by the commotion, were cautioned to return home. After making sure they were dead, the mob regrouped into their automobiles and disappeared by various routes leaving the victims hanging.

Late that night, the county Coroner was summoned and after collecting what little evidence there was, cut down the bodies. By morning there was a steady stream of onlookers and the police had to keep the crowds back, early arrivals were taking souvenirs of pieces of rope, bits of cloth from the scene.

The suspicion that the lynching party consisted of San Francisco policemen with inside information on the jail telephone system and the location of the suitable tree at the cemetery was published in the papers but ultimately neither the Coroner’s inquest nor the District Attorney could prove anything. No witnesses were forthcoming and the code of silence went unbroken until 1985 when a Healdsburg man contacted a local reporter, Gaye LaBaron, to tell the story.

The man, who, according to research done by the Bohemian newspaper using the Gaye LaBaron archive at Sonoma State, was one Clarence H. “Barney” Barnard. LaBaron, promised Barnard she would not reveal his identity until 10 years after his death. Barnard states that he was proud of being part of the lynching and that it was how things were done in the pioneer ways. The gang trained for three days for the jail break, they all wore black bandanas, carried arms, and smeared mud on their license plates.

“Everything was so well organized, everything went smooth … the first group to go in got the keys from the sheriff, the acting sheriff …” Barnard eagerly helped with the hanging, “You have to drag him off the ground, see. It takes several men to drag a man up. I know. I helped pull on one of the ropes and it was quite a job to get him off the ground. And it took him quite a while to asphyxiate, by not breaking his neck,” he said.

Barnard explained that the vigilantes were afraid that the court trial would “be a long drawn out deal. Look how it is now. Personally, I think the whole judicial system has fell apart, you know. … My grandparents come across the plains, and that’s the way it was. We shot [unintelligible] ourselves, and we had [to kill], and that’s the way they operated in them days, and if it hadn’t have, why, you know, there would be no law at all.”

A transcript of the Barnard interview by LaBaron can be found here.

Here is a short piece of the longer interview:

Barnard : So, him being such a good friend with my dad, when he was murdered in Santa Rosa why, this upset the town of Healdsburg, ‘cause he lived right here on Madison Street. And he was so popular that it didn’t take long for the people to get riled up and we had a leader that would organize it and he got us his good friend’s, Jim Petray’s good friends, together and we met at the back of the Standard Machine Works, you couldn’t see it from the street and we drilled for three nights, three different nights. And the Captain that had the experience in the army and things and [unintelligible]. And he wanted everything exact and he didn’t want a lot of people. He took, got 500 people in Healdsburg just like that, but you can’t control ‘em, so he only wanted around, not over 30 and he had them well disciplined. He was afraid if he got too many, why someone would get trigger happy and maybe shoot somebody or something, when they could avoid it.

There were implications in the interview that all of the lynchers were from Healdsburg and none were from San Francisco. The mention of the caravan of cars from San Francisco could have been an honest mistake by the press or a smoke screen. It is likely we’ll never know.

The Bohemian takes an adversarial view of mob justice, one which I think is appropriate and it reviews Sonoma County’s history of deaths by police force as well as while in custody. It is a bleak look, even during our modern era, the killing of a young Andy Lopez by Sonoma County Sheriff Gelhaus in 2013 is just one example.

Links to Gaye LaBaron’s December 8, 1985 article in the Press Democrat are here Part 1: Part 2:

Added:

A follow up column by Gaye LeBaron in the Press Democrat of January 5, 1986 is found here.